Construction Outlook

Concrete Basics 101: Foundational Knowledge for Modern Leaders

Concrete is the backbone of modern infrastructure and understanding its basics is crucial for shaping strategy in construction, development, and sustainability.

Learn all about concrete basics and clarity on cement vs concrete, how concrete is made, its history, strength types, structural and masonry uses, and more.

What is "Concrete"?

Concrete is a composite construction material composed of a fluid binder (cement mixed with water) combined with aggregates such as sand, gravel, or crushed stone. When this mixture cures (hardens), it forms a stonelike solid mass. Thanks to its strength and durability, concrete has become the world’s most widely used building material; it is even said to be the second most consumed substance on Earth after water. Modern concrete typically uses Portland cement as the binder, but ancient forms of concrete relied on other cementitious materials (like lime or gypsum) to bind aggregates into a solid form.

The word “concrete” comes from the Latin term concretus, meaning “grown together” or “condensed into a solid mass,” reflecting how the material’s ingredients coalesce into one whole. The term first appeared in English in the late Middle Ages with a general meaning of something tangible or solid that had grown together from (For example, a 1471 text uses “concrete” to describe a thing “which had grown together.”) Only much later did the word specifically refer to the building material. In fact, “concrete” as the name of the construction composite was not recorded until the early 19th century; one etymological source notes its first use in this sense around 1834. Before then, even though ancient Romans and others had used concrete-like materials, writers referred to those mixtures simply as cement, mortar, or other terms rather than “concrete.” Once the term took hold, however, it became the universal name for this essential construction material.

Cement vs. Concrete: What’s the Difference?

This brings us to a vital clarification: cement is not concrete. Cement is just one ingredient – like flour in bread. It’s a powder that reacts chemically with water to form a paste. Concrete, on the other hand, includes cement, water, aggregates (sand, gravel), and often admixtures to improve workability, durability, or setting time.

A “cement sidewalk” is incorrect; it should be a “concrete sidewalk.”

Using “cement” when we mean “concrete” leads to confusion – especially when specifying materials, ordering batches, or reporting sustainability metrics. Why does this distinction matter? Misunderstanding cement vs. concrete can lead to miscommunication in procurement and strategy. Leaders who grasp the difference can make informed decisions; for example, investing in concrete quality (mix design, curing) rather than just the cement supply.

Concrete as the Second Most Used Material

Concrete is so common that we hardly notice it. Yet by volume, it’s the second most used substance on Earth, after water; a fact that reframes planning and risk: small choices about mixes, durability, and delivery scale into outsized impacts on cities, economies, and project outcomes.

By volume, construction uses more concrete than all other materials combined because leaders value its practical advantages:

- Local sourcing: aggregates and cement are widely available.

- Versatility: cast almost any shape; scale from footpaths to dams.

- Performance: strong in compression; fire/heat resistance; familiar to crews.

- Composite power: with steel reinforcement, concrete handles bending and long spans.

These attributes, availability, versatility, and performance, explain why concrete remains the material of choice for foundations, frames, decks, and heavy infrastructure.

The History of Concrete

From ancient desert cisterns to megaprojects that shape modern skylines, concrete has long served as a vessel for human ambition. Its story is not one of invention, but of rediscovery: of unlocking nature’s chemistry to shape civilization itself.

6500 BC – The First Foundations

Concrete’s roots stretch deep into prehistory. As early as 6500 BC, Nabataean builders in the Middle East began crafting underground cisterns using lime-based mortars. In today’s Syria and Jordan, archaeological remains show these early engineers mixing burnt limestone, sand, and water to line water tanks–primitive versions of what we’d now call concrete. These builders weren’t just storing water. They were preserving life in one of the world’s driest climates, using materials that hardened into rock over time.

High angle view across the historic site of Petra, Jordan.

Centuries later, a different civilization took mortar to scale.

2600 BC – Binding the Pyramids

In Egypt, the construction of the pyramids brought massive limestone and granite blocks together using a gypsum-lime mortar. Though these weren’t concrete structures in the modern sense, they relied on chemical reactions between binder and water to hold the stones in place; proof that the Egyptians, too, understood the power of mineral-based cohesion. In places, nearly half a million tons of mortar helped create the Great Pyramid’s perfectly aligned edges, many of which remain intact over 4,000 years later.

At roughly the same time, another ancient society found its own solution.

Limestone blocks of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

221 BC – Lime and Sticky Rice on the Great Wall

In parts of China’s Qin Dynasty, builders mixed lime with glutinous rice to create an adhesive mortar that could hold bricks together through seasonal freeze-thaw cycles.

Remnants of this “sticky rice concrete” still cling to stonework on remote sections of the Great Wall, a testament to a fusion of agriculture and chemistry that was well ahead of its time. But it was the Romans who would bring concrete to its golden age.

200 BC to 476 AD – Rome Builds an Empire of Concrete

The Romans discovered that adding volcanic ash, pozzolana, to lime created a binder that could harden under water. This seemingly simple change unlocked a building revolution. With their invention of opus caementicium, they constructed aqueducts, temples, seawalls, and domes on a scale the world had never seen. Unlike stone, this new material could be poured into wooden molds, shaped into arches, and reinforced with layers of brick.

One of their most stunning accomplishments still stands today. The Pantheon in Rome, completed around 126 AD, features a 43.3-meter-wide dome made entirely of unreinforced concrete. The structure’s weight was reduced by using lighter aggregates toward the top; an early example of density engineering. Over 1,900 years later, it remains the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome, untouched by time or failure.

The Pantheon in Rome.

From the Colosseum to the ports of Portus, Roman concrete was more than a building too; it was a political weapon, a promise of permanence from a civilization that wanted to outlast history.

476-1400 – Concrete Forgotten

With the fall of the Roman Empire, much of this knowledge was lost to Europe. The art of making pozzolanic concrete faded, and builders returned to weaker lime mortars that lacked the durability of their Roman counterparts.

Medieval cathedrals and castles were assembled with great craftsmanship, but without the cohesive strength of concrete. The material receded into obscurity for nearly a thousand years.

Until, that is, a forgotten manuscript was unearthed.

1414 – Rediscovering the Roman Secret

In a dusty library, Renaissance scholars uncovered Vitruvius’s ancient text De Architectura, which included detailed notes on Roman building techniques. This rediscovery marked the beginning of concrete’s rebirth. Over the following centuries, architects and engineers began experimenting with ash, lime, and crushed brick to create mortars more resistant to weather and water.

But true progress would wait for the Enlightenment, and a stormy lighthouse.

1759 – Cement Returns to the Sea

When English engineer John Smeaton was asked to rebuild the Eddystone Lighthouse, he knew lime mortar wouldn’t survive crashing Atlantic waves. So, he tested mixtures of limestone and clay, eventually discovering a hydraulic binder that hardened underwater. His reconstruction of the lighthouse was a triumph, marking the first time in modern history that a synthetic hydraulic cement was purposefully designed and used in maritime construction. Concrete, reborn from science and necessity, was here to stay.

Smeaton’s Tower, The Hoe, Plymouth, England

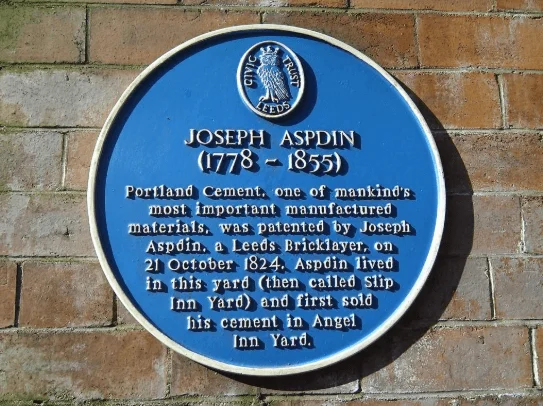

1824 – The Birth of Portland Cement

A few decades later, British mason Joseph Aspdin patented a new blend: Portland cement, so named for its resemblance to Portland stone. By burning finely ground limestone and clay together, he created a consistent, reliable binder that would become the backbone of modern concrete. It could be produced at scale, mixed predictably, and used in nearly every climate.

This was the moment that transformed concrete from an artisanal material into an industrial one.

1853–1903 – Iron and Sky

With the foundation in place, engineers began pushing limits. In 1853, French builder François Coignet embedded iron rods into concrete walls, creating the world’s first reinforced concrete building in Paris. No longer just strong in compression, concrete could now carry tension too. That opened the door to longer spans and higher walls.

By 1889, the Alvord Lake Bridge in San Francisco used reinforced concrete in its arches. And in 1903, the Ingalls Building in Cincinnati reached 16 stories, becoming the first concrete skyscraper. The material had left the ground and was beginning to rise.

1913-1936 – Mass Production and Monumental Thinking

The invention of ready-mix concrete in 1913 allowed builders to prepare fresh batches offsite and deliver them by truck; perfect for rapidly growing cities. Then came a project that defined the power of concrete in the industrial age: the Hoover Dam.

Completed in 1936, the Hoover Dam used more than 3.25 million cubic yards of concrete, so much that it had to be cooled from the inside out with embedded piping to prevent thermal cracking. Its sheer mass, curvature, and longevity proved that concrete could now shape not just buildings but entire landscapes.

1950s–1970s – Concrete Powers a New World

In the decades after World War II, concrete became the foundation of the global economy. From the highways of North America to Europe’s post-war reconstruction, to Asia’s megacities and industrial zones, concrete was poured at an unprecedented rate.

Prestressed and post-tensioned concrete expanded design possibilities, enabling bridges with record-breaking spans and slabs with minimal thickness. Cities reached skyward. Underground tunnels pushed deeper. And nuclear plants, bunkers, and space launch pads all relied on concrete’s unmatched versatility.

During this era, the material wasn’t just abundant. It was symbolic: of growth, modernity, and permanence.

1970s-2000s – Innovation and Environmental Awareness

As construction scaled globally, so did concerns about durability, efficiency, and environmental impact. Engineers began paying closer attention to concrete’s long-term behavior: chloride ingress, freeze-thaw cycles, sulfate attack, and alkali-silica reactions were better understood and mitigated through advanced mix design and new additives.

The use of Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs) like fly ash, slag, and silica fume became standard practice in high-performance mixes. These not only improved strength and durability but also reduced the embodied carbon of Portland cement. Large projects increasingly demanded concrete testing labs, curing controls, and better documentation of performance data.

At the same time, construction codes and international standards became more harmonized, preparing the ground for a more globalized construction market—one that would soon turn digital.

21st Century – Data, Durability, and Decarbonization

Today, concrete is no longer just poured; it’s monitored, modeled, and optimized. Modern projects integrate sensors to track temperature, strength, and curing progress in real time. Algorithms analyze past performance to design leaner, more durable mixes. Machine learning tools balance cost, carbon footprint, and schedule to meet increasingly strict sustainability targets.

Materials have also evolved. Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC) allows architects to design thinner, longer-lasting components with better resistance to abrasion and chemical attack. Carbon-mineralized concrete, which captures CO₂ during curing, has moved from the lab to commercial projects. Low-clinker cements now enable significant reductions in emissions while maintaining strength.

Concrete in the 21st century is lighter, smarter, and greener. Yet it still carries the legacy of those first Nabataean cisterns and Roman domes: to take soft earth and make it last forever.

Learning from the Past to Build the Future

History isn’t just a record: it’s a toolbox. The long journey of concrete, from Roman pozzolana to modern Portland cement to today’s embedded smart sensors, reveals a powerful truth: those who embrace innovation early tend to lead longer, stronger.

Consider the Romans. Their concrete structures, many still standing after nearly 2,000 years, weren’t just architectural feats; they were strategic assets. Their choice to use volcanic ash wasn’t aesthetic; it was smart engineering, enabling their empire to last. That’s the same mindset today’s construction leaders need.

Here’s the important distinction: not every mix of cement, aggregates, and water becomes concrete. It takes understanding of chemistry, materials, curing, and design to turn that mix into a resilient, high-performance material. That understanding is what drives modern innovation forward.

We’re not reinventing the wheel. Many of our best practices, like using pozzolans for durability, are echoes of ancient ingenuity. By knowing where concrete came from, today’s leaders can make more informed decisions: adopting high-performance mix designs, embracing real-time monitoring tools, and building for longevity, not just delivery.

Concrete is constantly evolving, and the most innovative builders evolve with it.

How Is Concrete Made?

Concrete may look simple: just gray sludge going into a form, but behind every pour is a sequence of carefully timed steps, chemical reactions, and human judgment. Yes, it starts with cement, water, and aggregates. But don’t be fooled.

Here’s the truth: any mix of cement, water, and stone isn’t automatically concrete.

Without the right ratios, placement, and curing knowledge, it’s just a slurry waiting to fail.

The important distinction is that concrete is a process. It’s what happens when raw materials are bound together with intention, experience, and scientific precision.

Where the Mix Begins

Concrete typically begins its journey at a batch plant, where cement, sand, gravel, water, and admixtures are measured and mixed to spec. In most modern projects, this arrives at the jobsite in the familiar spinning drum trucks, delivering what we call ready-mix concrete. For small jobs, concrete can be mixed on-site, but for critical structures, consistency is everything.

Once on site, the real choreography begins.

Step-by-Step: Making Cast-in-Place Concrete

Cast-in-place (or site-poured) concrete is exactly what it sounds like: concrete poured into forms right where the structure will stand.

Workers placing cast-in-place concrete with reinforcing steel in formwork. (courtesy of M. Chini, 2024)

- Formwork Preparation

Before any concrete arrives, formwork, usually plywood, steel, or plastic molds, is built to shape the structure. These forms must be tight and sturdy, holding thousands of pounds of wet concrete in place until it hardens.

- Reinforcement Placement

Next comes the rebar: steel rods or mesh designed to give concrete the tensile strength it naturally lacks. Think of it like bones in a body. Without reinforcement, concrete cracks under stretch or pull. With it, it becomes strong and flexible.

- Mixing & Pouring

The concrete mix arrives fresh. Workers pour (or pump) it into the forms, using vibrators to eliminate air pockets and make sure it flows into every corner. This step is time-sensitive: delays or improper placement can compromise strength and appearance.

- Initial Setting & Surface Finishing

In the first few hours, concrete transforms from fluid to firm. During this “setting window,” workers use tools like screeds and trowels to level and smooth the surface—whether it’s a floor slab, wall, or beam.

- Curing: Where the Magic Happens

Curing is not just drying. It’s a slow hydration reaction where cement and water form crystals that glue everything together. This process continues for weeks; but is most critical in the first 7 days. Improper curing (too dry, too cold, too fast) can reduce final strength by 30% or more. That’s why good crews monitor moisture, temperature, and time carefully.

In cold climates, heating blankets or insulated tarps are often used. In summer, water spraying or curing compounds retain moisture. Think of curing as raising a child: you don’t just feed it once and hope for the best.

- Form Removal & Strength Validation

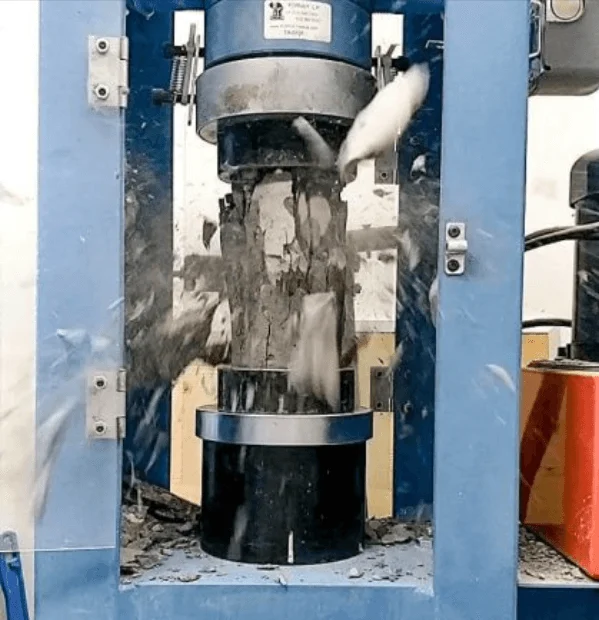

After a few days of curing, the concrete may look hard. However, is it strong enough to remove the formwork or apply loads? Traditionally, the answer came from breaking things on purpose.

Concrete contractors cast cylinder or cube samples during the pour, cure them under controlled conditions, and then send them to a lab for testing. At specific intervals (often 7 and 28 days), the samples are crushed in a machine to measure their compressive strength. Only once the strength met the design threshold would engineers give the green light to strip forms, apply loads, or proceed to the next construction phase.

This method works but it can be slow, labor-intensive, and doesn’t always reflect what’s happening inside the actual structure on site. That’s where modern technology steps in.

Maturity sensors, embedded directly in the concrete, continuously measure internal temperature and use that data to estimate strength in real time, without waiting for lab results or unnecessary delays. By using this approach, teams can strip forms earlier, post-tension sooner, and open roadways or decks ahead of schedule all while maintaining safety and structural integrity.

In today’s fast-paced projects, real-time strength tracking can improve concrete and project performance.

What About Precast?

Not all concrete is made on site. Precast concrete is cast and cured in factory-controlled conditions, then delivered to the job site. It offers speed, quality consistency, and weather protection; great for walls, columns, and highway barriers.

But cast-in-place still has advantages: it allows seamless connections (monolithic slabs, beams, and columns) that handle load transfer and complex shapes better than modular pieces. Many infrastructure projects today use hybrid systems, combining precast for repetition and cast-in-place for critical joints.

The Role of Admixtures

Concrete is not one-size-fits-all. Chemical admixtures are added to improve performance:

- Accelerators speed up setting in cold weather.

- Retarders slow down setting in hot conditions or long pours.

- Superplasticizers increase flow without adding water (key for congested rebar or pumpable concrete).

- Air-entraining agents trap microscopic bubbles that improve freeze–thaw durability.

- Corrosion inhibitors protect rebar in marine or de-icing environments.

These are how modern concrete adapts to climate, application, and construction timelines.

Concrete is planned. Knowing how it’s made helps you avoid costly delays, defects, and rework. Mistakes in formwork, curing, or mix design can turn a 28-day project into a 6-week scramble. But when done right, strategic control of concrete work accelerates schedule, improves quality, and strengthens ROI; literally and financially.

Understanding Concrete Strength: Beyond Just the Numbers

When people talk about concrete, the first thing they mention is strength. But in truth, “strength” isn’t a single number on a report; it’s a whole family of qualities that determines how concrete performs in the real world.

You’ll hear words like compressive strength, tensile strength, flexural strength, and early-age strength tossed around. Here’s what they really mean and why they matter to anyone building, buying, or managing concrete structures.

Compressive strength is the headline act. It tells us how much squeezing force (compression) a chunk of concrete can withstand before it breaks. This is what labs measure by crushing concrete cylinders or cubes in a press; usually at 28 days after pouring. For context, everyday sidewalk concrete might hit 20 MPa (about 3,000 psi), while high-rise columns often require 40 MPa (nearly 6,000 psi), and some special mixes for bridges and towers can push past 100 MPa.

But concrete has an Achilles’ heel: tensile strength. Pull on it, and it’s surprisingly weak; only about a tenth as strong as it is in compression. That’s why we add steel rebar. Think of it like concrete’s secret sidekick: concrete handles the heavy pushing and squeezing, steel takes the pulling and stretching. Engineers check tensile strength with split-cylinder tests or by seeing how much a concrete beam can bend before it snaps.

Flexural strength is a close cousin, showing how well concrete can handle bending. This is especially important for things like highways and industrial floors, where big loads might try to crack slabs right down the middle. Pavement engineers, for example, look for flexural strengths of 4–5 MPa (about 600–700 psi) for reliable, crack-resistant surfaces.

Then there’s early-age strength. On a jobsite, waiting four weeks to see if a slab is strong enough just isn’t practical. Fast-track projects often demand mixes that hit 15 MPa (2,200 psi) or more in just 24 hours; thanks to specialty cements, admixtures, or even steam curing. Early strength isn’t just about schedule; it’s about keeping projects moving, stripping forms sooner, and reducing construction risk in cold weather.

Of course, strength isn’t a one-time event. Ultimate strength is the highest load the concrete will ever need to resist, but service strength, the loads it actually sees in daily use, is lower. Engineers build in safety factors to make sure structures have a cushion. And while the 28-day number is the industry gold standard, concrete doesn’t stop strengthening there: some mixes keep gaining muscle for months or even years, especially if they use fly ash or other supplementary cementitious materials.

Lab technician preparing a concrete cylinder for compressive strength test. These cylinders (usually 150 mm × 300 mm) are crushed at set intervals to ensure the concrete meets its design strength for safety and compliance.

Why do these numbers matter? Because every project is different. A patio might only need 20 MPa, while a bridge pier or high-rise core could demand 70 MPa or more. Going overboard with strength isn’t always the answer: high-strength mixes cost more (more cement, more admixtures, more testing), and sometimes the extra cement can actually make concrete more brittle or more prone to cracking. It’s about balancing safety, performance, and cost; choosing the strength you need, and not overspending for strength you don’t.

Reinforcement is part of the equation. Good concrete alone isn’t enough; if the rebar is low quality or poorly placed, the structure’s strength is compromised. It’s the bond between steel and concrete that gives us the versatility to build skyscrapers, bridges, and massive slabs.

Different mixes serve different roles.

- Normal Strength Concrete (NSC): 20-40 MPa; perfect for floors, residential construction, and mass housing.

- High-Strength Concrete (HSC): Over 50 MPa; essential for high-rises, long-span bridges, and heavy-duty infrastructure.

- Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC): 120 MPa and beyond, with fibers for durability and toughness. These enable architects to create slender, elegant forms and deliver extended service life, though at a premium price.

Specifying the right concrete strength is a strategic decision. Stronger mixes can mean thinner columns, more rentable floor space, or even an extra story on your building. But overdoing it can drain the budget and ramp up the carbon footprint (more cement = more emissions). The real win comes from optimizing for your true needs; and using today’s technology to get it just right.

With maturity sensors and in-place monitoring, you can actually track strength as it develops, allowing for more precise decision-making and tighter schedules. Instead of relying on a generic 28-day rule, you’ll know exactly when your concrete is ready to work, saving days or even weeks across a project.

Understanding concrete strength is about more than hitting a number. It’s about asking, “What performance do we actually need? How do we get there efficiently, reliably, and sustainably?” The smartest teams keep questioning, keep measuring, and keep building for the future.

Testing early-age strength is important!

Find out the six major causes of low concrete breaks that can delay your project timelines.

Strength or Performance

When talking about concrete, it’s easy to focus on strength alone. But here’s a crucial truth: strength and performance aren’t always the same thing. Strength is just one number on the test report: how much force the concrete can withstand before it fails. Performance, on the other hand, is about how well the concrete does its job in the real world. Does it resist freezing and thawing? Can it stand up to road salts, heavy truck traffic, or aggressive chemicals? Does it last decades without crumbling or cracking? Sometimes, chasing the highest possible strength is a mistake. A concrete mix designed for extreme strength might dry out too quickly, shrink and crack, or be more brittle under impact. Instead, the smartest builders and project owners start with the question: “What performance do we actually need for this structure?” and then select the right combination of strength, durability, and workability. That’s how you get concrete that doesn’t just test well, but actually performs over its full lifetime.

Testing & Evaluation: From Truck to Long-Term Performance

Concrete disappears behind forms and finishes but its quality shouldn’t be a mystery. A clear testing plan, tied to recognized standards, tells you if the mix you ordered is the mix you received, and whether it will perform over its lifetime.

Below is an organized roadmap of fresh concrete tests (done at delivery/placement) and hardened concrete tests (done later for strength and durability), with example specification windows so teams know what “good” looks like.

A. Fresh Concrete (at the truck / during placement)

1) Slump – Workability

-

- Standard: ASTM C143 (slump). For SCC, use ASTM C1611 (slump flow).

-

- What it checks: Consistency/workability; indirect check on water content.

-

- Typical spec windows (examples):

-

-

- Conventional placements: 75–125 mm (3–5 in).

-

-

-

- Pumped/complex rebar: 100–200 mm (4–8 in).

-

-

-

- SCC (slump flow): 550–750 mm (22–30 in) with stability checks (e.g., Visual Stability Index ≤ ~1; project specific).

-

-

- Why it matters: Too low = hard to place/finish; too high = risk of segregation, lower strength.

-

- Freeze-Thaw Durability

-

- Standards: ASTM C231 (pressure method), ASTM C173 (volumetric method).

-

- What it checks: Percent of intentionally entrained microscopic air.

-

- Typical targets (examples):

-

-

- Freeze-thaw exposure: 4-8% (target depends on aggregate size and exposure class).

-

-

-

- Interior/non-air-entrained concretes: ~1-3% (entrapped air only).

-

-

- Trade-off: More air improves freeze–thaw durability but reduces compressive strength.

-

- Standard: ASTM C1064.

-

- What it checks: Concrete temperature at delivery/placement.

-

- Typical acceptance window (examples): 50-90 °F (10-32 °C); project specs may allow different limits for hot/cold weather concreting.

-

- Why it matters: High temps accelerate set and can raise cracking risk; low temps slow strength gain.

-

- Standard: ASTM C138.

-

- What it checks: Fresh density; calculates yield and air by mass.

-

- Typical values (examples):

-

-

- Normal weight: 137-150 lb/ft³ (~2200-2400 kg/m³).

-

-

-

- Structural lightweight: 85-115 lb/ft³ (~1350-1850 kg/m³).

-

-

- Standards: ASTM C31 (field-made cylinders) → lab cure/testing later.

-

- Purpose: Creates the official samples used for strength acceptance (see C39 below).

-

- Setting time (penetration): ASTM C403 (useful for schedule/formwork planning).

-

- SCC stability & passing ability: ASTM C1611 (slump flow), ASTM C1621 (JRing), visual stability checks.

-

- Standard: ASTM C39 (cylinders); common ages 7 & 28 days (others by spec).

-

- Typical classes (examples): 20–40 MPa (3–6 ksi) for general work; >50 MPa (>7.25 ksi) for high-rise/bridge elements.

-

- Acceptance (example, per ACI practice): Average of three consecutive tests ≥ f’c; no single test

-

- Why it matters: Primary safety check for loadbearing capacity.

-

- Standard: ASTM C1074 (maturity method).

-

- What it does: Estimates in-place strength from time-temperature history (sensor or data logger), using a project specific calibration curve.

-

- Use cases: Early formwork removal, post tensioning, opening to traffic with confidence.

-

- Standards: ASTM C78 or C293 (flexural); ASTM C496 (splitting tensile).

-

- Typical values (examples): Pavements often target flexural 4-5 MPa (600-700 psi). Splitting tensile ≈ 6–12% of compressive strength (mix-dependent).

-

- Standard: ASTM C42.

-

- Use: Verifies in-place strength when cylinders underperform or for existing structures.

-

- Common acceptance guidance (example): Average of three cores ≥ 85% f’c; no single core

-

- Rapid Chloride Permeability (RCPT): ASTM C1202; total charge passed (coulombs) over 6 h.

-

-

- Typical interpretation (example ranges):

-

-

-

-

- > 4000 = High; 2000-4000 = Moderate; 1000-2000 = Low; 100-1000 = Very Low;

-

-

-

- Bulk Electrical Conductivity/Resistivity: ASTM C1760 (bulk); Surface Resistivity AASHTO T358.

-

-

- Rule of thumb: Higher resistivity / lower conductivity ⇒ lower chloride penetrability.

-

-

-

- Example project screen: Surface resistivity > ~20 kΩ·cm often flags low penetrability (confirm owner/agency criteria).

-

-

- Standard: ASTM C876 (half-cell potentials vs Cu/CuSO₄).

-

- Typical interpretation: Potentials more negative than −350 mV → high probability of active corrosion; more positive than −200 mV → low probability. The -200 to -350 mV band is uncertain and needs corroborating tests (chlorides, resistivity, cover).

-

- Standard: AASHTO T260 (acid soluble chlorides).

-

- Example limits (water-soluble, by wt. of cement; check ACI 318 table for governing values):

-

-

- Prestressed: ≤ 0.06%; Reinforced, moist/exterior: ≤ 0.15%; Reinforced, interior/dry: ≤ 0.30%; Plain: ≤ 1.00%.

-

-

- Standard: ASTM C666 (rapid freeze-thaw).

-

- Example acceptance: Relative Dynamic Modulus ≥ ~80% after 300 cycles; limited mass loss (project specific).

-

- Standard: ASTM C1012 (sulfate attack-length change).

-

- Use: Compare expansion vs time; specify low expansion limits for severe sulfate exposures.

-

- Rebound hammer: ASTM C805 (screening uniformity; not for acceptance strength).

-

- Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity: ASTM C597 (cracking/quality uniformity).

-

- Petrography: ASTM C856 (forensics: ASR, paste quality).

-

- Condition scanning: GPR, IR thermography, cover meters (rebar location/cover, delamination).

Overview of Spec Windows

| Property / Test | Standard | Example Target / Interpretation |

| Slump (conventional) | ASTM C143 | 3-5 in (75-125 mm) |

| Slump flow (SCC) | ASTM C1611 | 22-30 in ( 550-750 mm); check stability/passing |

| Air content (FT exposure) | ASTM C231/C173 | 4-8% (size/exposure dependent) |

| Temp at delivery | ASTM C1064 | 50-90 °F ( 10-32 °C) typical window |

| Unit weight (normal) | ASTM C138 | 137-150 lb/ft³ (2200-2400 kg/m³) |

| Compressive strength | ASTM C39 | Per spec class (e.g., 30-40 MPa at 28 d) |

| Cylinder acceptance (example) | ASTM C39 + code | Avg of 3 ≥ f’c; no single |

| In-place strength (maturity) | ASTM C1074 | Calibrated curve; real-time estimates for stripping/PT |

| Flexural strength (pavement) | ASTM C78/C293 | ~4-5 MPa (600-700 psi) typical |

| RCPT charge (6 h) | ASTM C1202 | >4000 High; 2000-4000 Mod; 1000-2000 Low; 100-1000 Very Low; |

| Surface/bulk resistivity | AASHTO T358 / ASTM C1760 | Higher kΩ·cm ⇒ lower chloride penetrability (e.g., > ~20 kΩ·cm = low) |

| Half-cell potentials | ASTM C876 | -200 mV: low |

| Freeze-thaw durability | ASTM C666 | RDM ≥ ~80% after 300 cycles (project specific) |

| Sulfate expansion | ASTM C1012 | Meet project expansion limits by exposure class |

| Chloride content | AASHTO T260 (+ ACI limits) | ≤ 0.06% prestressed; ≤ 0.15% moist/exterior reinforced; ≤ 0.30% interior; ≤ 1.00% plain |

These values are common examples to guide discussion and submittals. Always confirm governing project specifications, agency criteria (DOT/owner), and code (e.g., ACI 318/CSA A23.1, EN).

What This Means for Your Project

A disciplined test plan is risk control. Fresh concrete tests prevent bad placements. Hardened and durability tests protect lifecycle value. Pair standardized lab results with in–place monitoring (e.g., maturity) and periodic condition assessments, and you’ll shave days off the schedule, cut rework, and document quality for audits and claims. In short: test early, test right, and keep testing smart.

Explore construction quality and compliance in concrete testing labs!

Check out our comprehensive blog on testing labs, including practical roles, reports, QA/QC cadence, and more.

Durability & Deterioration: Design for the Environment First

Concrete can last a century or fail in a decade. The difference isn’t “more strength.” It’s durability: how well the mix and the details resist real–world exposure (water, salts, freeze–thaw, chemicals, heat) over time. For decisionmakers, this is the big shift: let durability govern your mix design, then set strength to match the structural need. That order saves money, time, and carbon across the life of the asset.

What is Durability?

Durability is a concrete’s ability to resist weathering, chemicals, abrasion, and time while staying safe and usable. Major codes often target 50-100 years of service life for key infrastructure, but you only get there by controlling permeability, protecting steel, getting the air void system right (in cold regions), and curing properly.

Key Levers You Control (these should drive the mix design and specs):

- Water-to-cementitious ratio (w/cm): Lower w/cm ⇒ lower permeability ⇒ slower chloride/carbonation ingress.

- Supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs): Fly ash, slag, silica fume, calcined clays improve density and durability.

- Air entrainment (cold climates): Micro air system prevents freeze-thaw scaling.

- Concrete cover over rebar: More cover = more time before steel is reached by chlorides/carbonation.

- Curing quality: Proper moisture/temperature early on locks in durability.

- Performance screens: Use RCPT (ASTM C1202), resistivity (AASHTO T358 / ASTM C1760), half-cell potentials (ASTM C876), freeze-thaw (ASTM C666), sulfate expansion (ASTM C1012), ASR screening (ASTM C1260/C1293), and carbonation depth (regional/EN methods such as EN 14630/RILEM).

Key Deterioration Mechanisms in Reinforced Concrete and Design Countermeasures

1) Rebar corrosion (chlorides & carbonation)

What happens: Chlorides (de-icing salts, seawater) or carbonation (CO₂ lowering concrete pH) reach the steel. The steel rusts, expands, and cracks the cover; spalling follows.

Design to resist:

- Marine/bridge decks: w/cm ≤ 0.40; SCMs (e.g., 25–50% slag or 20–30% Class F fly ash); cover ≥ 50–75 mm (2–3 in) per code; target RCPT ≤ ~2000 coulombs (ASTM C1202) or surface resistivity ≥ ~21 kΩ·cm (AASHTO T358).

- Measure & monitor: RCPT/Resistivity; half-cell potentials (ASTM C876); chloride content (AASHTO T260).

- Measure & monitor: RCPT/Resistivity; half-cell potentials (ASTM C876); chloride content (AASHTO T260).

Minneapolis I-35W Bridge Collapse (2007)

On August 1, 2007, an eight-lane, three-span section of the I-35W Bridge across the Mississippi River in downtown Minneapolis collapsed at approximately 6:00 p.m. It was crowded with rush hour traffic. The final death toll was 13. The bridge was being eroded by corrosive salt chemicals. The bridges usually are resistant to these chemicals. The steel was unable to withstand the severe erosion.

2) Freeze-thaw damage (cold climates)

What happens: Water in pores freezes and expands, cracking the paste and scaling the surface.

Design to resist:

- Air entrainment: ~4-7% (ASTM C231/C173), tuned to aggregate size and exposure.

- Low w/cm: Typically ≤ 0.45 with SCMs for denser paste.

- Verify: ASTM C666 (freeze-thaw), ASTM C672 (scaling). Keep the fresh air within spec every truckload.

(courtesy of M.Chini,2025)

3) Alkali-silica reaction (ASR)

What happens: Alkalis in the paste react with certain aggregates, forming a gel that swells with moisture and cracks concrete internally (map cracking, joint growth). Since it appears after several years of exposure; and once it does, it’s often already spread through most of the concrete; it’s usually considered a form of “concrete cancer.”

Design to resist:

- Prequalify materials: ASTM C1260/C1293 to screen aggregate reactivity and mitigation.

- Mitigate: Limit cement alkalis (Na₂Oeq), use SCMs (Class F fly ash, slag, silica fume, natural pozzolans), and manage moisture pathways (sealants/drainage).

- Monitor: Petrography (ASTM C856), expansion tracking, and condition surveys.

4) Sulfate attack (soils/groundwater, wastewater)

What happens: Sulfates attack the paste (ettringite/thaumasite formation), causing expansion and softening.

Design to resist:

- Binder choice: Type V / HS cements, or blended systems with lowC₃A; SCMs that lower permeability and C₃A reactivity.

- Verify: ASTM C1012 expansion limits; w/cm ≤ ~0.45 and adequate cover.

5) Abrasion & erosion (decks, spillways, industrial floors)

What happens: Traffic or high velocity water removes paste and exposes aggregate.

Design to resist:

- Hard, dense surface: Proper finishing and curing; harder aggregates; surface hardeners where appropriate.

- Specs: Minimum strength may help, but finishing quality, curing, and aggregate selection usually govern.

6) Chemical attack (acids, industrial chemicals)

What happens: Acids dissolve cement paste; some solvents/oils damage surfaces.

Design to resist:

- Barrier first: Coatings/liners; chemical-resistant mortars.

- Binder tweaks: Some SCMs and polymer-modified systems improve resistance, but protection systems usually do the heavy lifting.

A Durability-First “Spec Menu”

| Exposure | Primary Risks | Mix & Detailing Levers | Example Performance Screens |

| Marine / de-icing salts | Chlorides → rebar corrosion | w/cm ≤ 0.40; 25–50% slag or 20–30% Class F fly ash; cover ≥ 50–75 mm; high quality curing | ASTM C1202 ≤ ~2000 coulombs or AASHTO T358 ≥ ~21 kΩ·cm; ASTM C876 potentials trending > -200 mV (low risk) |

| Cold climate pavements | Freeze–thaw scaling | Air entrained 4–7% (ASTM C231/C173); w/cm ≤ 0.45; proper finishing/curing | ASTM C666 relative dynamic modulus ≥ ~80% after 300 cycles; ASTM C672 acceptable scaling rating |

| ASR-susceptible aggregates | Internal expansion/cracking | Verify aggregate (ASTM C1260/C1293); limit alkalis; use SCMs (Class F, slag, silica fume) | Expansion below project limits in C1260/C1293; confirmation by ASTM C856 petrography |

| Sulfate soils/effluent | Paste expansion/softening | Type V/HS cement or low C₃A blends; SCMs; w/cm ≤ ~0.45; drainage | ASTM C1012 expansion within limits over test duration |

| Industrial floors / spillways | Abrasion/erosion | Dense surface, hard aggregate, good curing; surface hardeners | Owner acceptance by mass/height loss (project specific), plus mock-ups and wear tests |

These are orientation values. Your final criteria come from owner specs, ACI/CSA/EN standards, and exposure classes defined for the project.

When durability drives the spec, you cut lifecycle cost, reduce downtime, and avoid emergency repairs. It also lowers embodied carbon—because the greenest structure is the one you don’t have to rebuild. Set the exposure, pick the durability levers, then size the strength. That order is how long–lived, low–risk concrete gets built.

Enhance your concrete durability with smart technology.

Learn all the challenges of achieving concrete durability in construction in our webinar.

How to Cut Carbon Without Compromising Performance

Concrete is everywhere—and that scale is why sustainability matters. Cement (the binder in concrete) is responsible for about 8% of global energy-related CO₂ emissions, largely from heating limestone and the chemical reaction that releases CO₂ during clinker production. At the same time, the world uses ~4.5 billion m³ of concrete per year, so even small improvements add up.

Key idea: Design for durability performance first (chloride resistance, carbonation resistance, sulfate exposure, freeze–thaw) using performance-based specs. Once durability targets are locked, use low carbon levers (PLC/Type IL, SCMs, optimized w/cm, AI mix tuning) to minimize cement and embodied carbon without risking long-term performance. SWFWMD

Where Does the Carbon Come From?

- Clinker is the main source of CO₂ in cement and therefore in concrete. Reducing clinker per cubic meter of concrete (the clinker factor) is the most direct path to lower embodied carbon. Portland limestone cement (PLC, Type IL), which intergrinds 5–15% limestone, typically cuts CO₂ ~10% per ton of cement versus ordinary Type I/II, with comparable performance when properly specified. cement.org

- Scale matters: With ~4.5 billion m³ placed annually, shifting even part of the market to PLC and SCM-rich mixes yields meaningful global impact.

Approaches to Reduce Embodied Carbon with Low-Carbon Materials

1) Lower Clinker Cements (PLC and New EN Blends)

- PLC / Type IL (ASTM C595): 5-15% interground limestone; ~10% CO₂ reduction vs. Type I/II cement, widely adopted across North America.

- Europe’s EN 1975: expands composite cement families CEM II/CM and CEM VI to enable much lower clinker factors at scale (including calcined clay + limestone combinations).

2) Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs): Match the SCM to the Durability Need

Using SCMs safely lowers clinker content and improves durability (lower permeability, better sulfate resistance, lower heat); key for lifecycle performance.

At a glance SCM guide (typical ranges & durability value):

| SCM | Primary Durability/Value | Typical Replacement† | Regional Notes (Availability) |

| Fly ash (Class F/C) | Lowers permeability; ASR mitigation (Class F); helps workability, laterage strength | 15-30% common (can be higher with testing) | North America: supply tightening as coal plants retire; consider harvested ash or alternatives. |

| Slag cement (GGBFS) | Strong chloride resistance; sulfate resistance; lower heat | 30-50% typical | Europe/Japan/US: widely used; Japan reports >20% of cement output as blast furnace slag cements. |

| Silica fume | Ultra-low permeability; high strength | 5-10% | Used in marine/bridge decks/UHPC where very low ion transport is required. |

| Calcined clay + limestone (LC³) | 30–40% CO₂ reduction at cement level with comparable performance when properly designed | Up to ~50% clinker replacement (as CEM II/CM) | Scaling in Europe/Asia; supported by EN 1975; field pilots in India. |

| Ground glass pozzolan (GGP) | Improves permeability & ASR resistance; circularity (glass diversion) | 10-30% (project specific) | Now standardized as ASTM C1866; growing availability in North America. |

| Rice husk ash (RHA) | High reactivity silica; enhances durability in tropical markets | 5-15% (optimize via testing) | Emerging in Asia Pacific; growing literature on durability gains and optimum dosages. |

Note: Typical ranges vary with exposure class, cement type, and testing. Always verify durability performance (e.g., AASHTO T358 surface resistivity or ASTM C1202 RCPT) at the specified age.

3) Carbon Smart Curing and CO₂ Utilization

- CO₂ mineralization in fresh concrete: Injecting CO₂ during mixing can form stable calcium carbonate in the paste, often allowing cement reduction at equal strength. Documented at scale (e.g., Amazon HQ2 >1,000 t CO₂ saved across placements).

- CO₂ curing of blocks/units: Precast plants can cure with CO₂ to permanently mineralize a portion of CO₂ and improve early strength in masonry units; multiple commercial systems are in market.

4) Carbon Capture on Cement Kilns (CCUS)

Industrial-scale capture has started. In Brevik, Norway, the first large cement plant CCS project is now online, capturing CO₂ for storage and showing a pathway to deep decarbonization at the kiln.

5) Alternative Binders (Targeted Use Today)

- Geopolymers (alkali-activated binders): LCA studies report ~40-80% CO₂ reduction vs. OPC concrete (varies with activators, supply chain, and cure). Use where standards/owners permit and durability testing supports the application.

- Magnesia-based and other novel cements: Magnesia-based cements and binders are relatively unstudied systems, but they are gaining more interest since most of the MgO raw materials are not in carbonate forms.

Performance-Based Specs: Lead With Durability (then Lower Carbon)

Concrete that fails durability costs more (repairs, outages) and emits more over its lifecycle. Specify the performance you need (permeability, resistivity, sulfate resistance, carbonation cover) and then optimize for carbon inside those guardrails.

As an example in designing for concrete decks in marine environments, by locking permeability (via resistivity/RCPT) instead of only specifying compressive strength, you nudge mix designs toward lower cement, lower carbon solutions that last longer.

Construction Phase Efficiency: Optimize What You Pour

Sustainability isn’t just material science; it’s also about how we use concrete:

- AI-assisted mix optimization: Producers are using plant-to-pour data and AI to reduce cement content while holding performance steady, at scale, by tuning blends against historical strength and durability data.

- Real-time QA/QC: In-situ maturity and temperature sensors help avoid overconservative wait times and reduce rework and waste, supporting schedule and sustainability outcomes. (Maturity is standardized in ASTM C1074; many DOT specs already permit it.)

- Recycled Concrete Aggregate (RCA): For pavements and select structural applications, DOTs have documented successful use of RCA; lowering virgin aggregate demand and trucking. Follow FHWA guidance and verify performance.

One More Nuance Leaders Should Know: “Recarbonation”

Over its life, and especially when crushed at end–of–life, concrete reabsorbs some CO₂ from the air through carbonation, which partially offsets kiln emissions. Accounting methods are improving, and major industry tools now include uptake in EPDs. This does not excuse over cementing; it simply means long–lived, well–designed concrete can have a lower net footprint than older inventories assumed.

Digital Transformation: A Simple Field Guide from Plant to Pour to Proof

The concrete industry is moving fast into the digital age. For leaders, that doesn’t mean more gadgets for their own sake, it means fewer delays, clearer decisions, and better performance. Here’s a plain language walkthrough of how digital tools now support each stage: production, transportation, pouring/placing, and monitoring.

1) Production: Smarter at the Batch Plant

What happens: Cement, aggregates, water, and admixtures are measured and mixed to the project’s recipe.

How digital helps

- Moisture & inventory sensors: Real-time moisture in sands and aggregates means the water-to-cementitious ratio stays on target: no accidental “wet” batches that hurt strength and durability.

- Automated batch controls: Computerized dosing and live dashboards reduce human error and keep every truck consistent.

- Recipe analytics: Producers analyze past results (strengths, temps, durability tests) to finetune cement content and SCM blends, often achieving the same performance with less cement.

- EPDs at the plant: Many producers now generate Environmental Product Declarations for mixes, so owners can compare embodied carbon (kg CO₂e/m³) alongside cost.

This is where schedule and carbon are won or lost. Better control at the plant means fewer rejections on site and more predictable formwork cycles.

2) Transportation: Quality in the Truck

What happens: The mix leaves the plant in a revolving drum truck and arrives at site ready to place.

How digital helps:

- E-ticketing & GPS: Everyone sees the same delivery time, route, and ticket data (mix ID, batch time, slump target). Fewer phone calls. Fewer surprises.

- In-transit adjustments: With approval, drivers can add admixtures (not water) to maintain workability during long hauls or heat. The target is consistent slump/workability without diluting strength.

- Temperature tracking: Truck sensors (or quick checks on site) confirm the concrete is in the right temperature range for placing which is critical in hot or cold weather.

Transparency here shrinks waiting, claims, and rework. It also improves safety (less onsite traffic jam and confusion).

3) Pouring & Placing: From Forms to Finish

What happens: Crews place concrete into forms, consolidate it (remove air pockets), finish the surface, and start curing.

How digital helps:

- Pre-pour checklists in the cloud: Formwork, rebar, embeds, and test frequencies are confirmed in shared apps, so the pour starts right.

- Onsite fresh concrete tests logged live: Slump (workability), air content (for freeze–thaw regions), temperature, and unit weight are recorded on tablets; the project team can approve in real time.

- Weather & thermal planning: Forecasts plus thermal modeling help time the pour, choose blankets or cooling pipes for large placements, and avoid cracking from temperature differences.

- Finishing & curing discipline: Digital curing plans (spray schedule, blanket usage, or curing compounds) and photo logs show owners the work was done correctly; useful for audits and claims.

Field tip: Workability ≠ water. If slump is low, ask for a water-reducing admixture rather than adding water. You’ll keep strength and durability on track.

4) Monitoring & Closeout: Proof, Not Guesswork

What happens: The concrete hardens and gains strength; first days are critical, but performance matters for decades.

How digital helps:

- Traditional acceptance (baseline): You still cast cylinders and break them in a lab (e.g., at 7 and 28 days) to verify compressive strength. Those results remain the contract baseline.

- In-place strength in real time: Maturity sensors embedded in the pour track internal temperature and apply the ASTM C1074 method to estimate strength inside the element itself. That lets teams strip forms, post-tension, or open to traffic at the earliest safe moment, often days sooner than waiting for lab breaks alone.

- Mass pour thermal control: Sensors watch temperature differentials through thick sections to prevent thermal cracking risk; alerts trigger cooling or insulation adjustments.

- Drying & flooring readiness: Interior slabs can be monitored for temperature/humidity trends to plan coverings at the right time, avoiding blistering or adhesives failures.

- As-built data for lifecycle value: Sensor records, test results, and pour logs flow into digital closeout (and even a BIM model). Years later, facilities teams can see exact curing/strength history of each element for renovations, loads, or forensics.

Putting it Together: A Simple “Smart Concrete” Workflow

- Design the mix with data (proper w/cm, SCMs, and admixtures for the exposure).

- Batch with controls (moisture sensors, automated dosing, plant dashboards).

- Deliver with visibility (e-ticketing, real-time status, temperature checks).

- Place with discipline (fresh tests logged live, thermal plan, proper curing).

- Verify in place (maturity sensors + lab breaks) and hand off digital records for long-term value.

Why this matters:

- Speed with certainty: Real-time strength and temperature data trim days from formwork cycles and critical path activities, without adding risk.

- Quality you can prove: Digital records make disputes rare and audits easy.

- Lower cost & carbon: Better control reduces cement overuse, rework, and waste.

- Talent magnet: A data-driven jobsite attracts the next generation of engineers.

Digital tools don’t replace concrete know-how: they amplify it. When teams see what’s happening inside the pour, they make better calls, finish sooner, and hand owners a durable asset with a digital paper trail to match.

Lifecycle of a Concrete Element

A concrete element doesn’t “end” when it hardens. It moves through design → construction → service → renewal, and each stage has budget levers that shape performance and total cost of ownership. One practical takeaway for domestic projects (houses, driveways, patios, small plazas): concrete is usually a modest slice of the overall construction budget, but it carries an outsized share of structural reliability and durability risk. That’s why a little more discipline in mix design, curing, and monitoring pays off for decades.

1) Design Phase: Set performance first, then strength

Everything starts on the drawings (or in the BIM model). Engineers size the element and place reinforcement, but lifecycle thinking lives in the details:

- Durability choices: pick the right water-to-cementitious ratio, specify SCMs (e.g., fly ash/slag/silica fume), set adequate concrete cover to reinforcement, and detail drainage so water doesn’t sit where it can do harm.

- Plan for the future: add embeds and access points for inspection; consider whether openings or heavier loads might come later.

Example: A parking garage beam (or plaza slab over occupied space) with an extra 0.5″ of cover and a corrosion-inhibiting admixture costs a little more up front but often delays the onset of corrosion; stretching service life before major repair is needed.

2) Construction Phase: Execute the recipe and document it

Once you mobilize, most of the element’s lifetime value is created -or lost- on site.

- Quality control: verify the delivered mix matches the spec; place and consolidate properly; cure to maintain moisture and temperature in the early days. Poor curing can create microcracking and shorten life.

- Records that matter: capture what was actually poured: mix IDs, test results, pour times, and curing method.

- Create a “medical record”: tag elements in a database (linked to BIM if you have it) with birth data and any sensor records. That history pays off later when you evaluate changes or repairs.

3) Operation / Service Phase: Inspect, maintain, and adapt

For decades, the element does its job. A light, steady maintenance plan keeps it that way.

- Inspection & monitoring

Schedule regular walkthroughs for cracks, spalls, ponding, and leaks. On critical assets (garage slabs, bridge decks, plaza slabs over rooms), embedded sensors can flag temperature/humidity trends or corrosion risk long before you see damage at the surface.

- Maintenance actions

Seal cracks early; renew protective coatings or membranes on a cycle; consider cathodic protection where salt exposure is severe. A bit of timely maintenance prevents small issues from turning into structural repairs.

- Use changes

If loads increase (e.g., storage on a floor designed as office) or new codes apply, evaluate capacity with NDT and analysis. Strengthen with steel plates, overlays, or FRP wraps when it’s cheaper and faster than replacement.

- Case reminder (corrosion risk): The Surfside condo collapse (Florida, 2021) highlighted how long-term water ingress and reinforcement corrosion can undermine flat plate systems. Coastal exposure, deferred repairs, and compromised connections together raised the risk; underscoring why routine inspection and timely remediation are essential in aggressive environments.

- Case reminder (material limits): The UK’s RAAC school roof crisis showed how a short-life material (reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete panels from mid-century construction) can exceed its design life, absorb moisture, and lose capacity, forcing emergency closures and shoring. The lesson is simple: know the limits of the material you have, inspect accordingly, and act before visible distress becomes structural.

4) End-of-Life Phase: Repair, reuse, or recycle

Eventually you’ll face renewal: by repair, adaptation, or replacement.

- Deconstruction, not just demolition

When replacement wins, plan to segregate materials. Concrete can be crushed and used as recycled aggregate or base; reinforcing steel is readily recycled.

- Adaptive reuse

Often, the fastest and lowest carbon path is to keep the concrete frame and adapt the function: turning a sturdy shell into new offices, housing, or labs with targeted strengthening. This preserves embodied carbon and avoids months of waste hauling.

- Waste management & circularity

Where concrete truly becomes waste, send it to authorized recyclers. Many cities now treat concrete debris as a resource for new fill and aggregate. Include diversion targets in contracts (e.g., “≥80% by weight diverted from landfill”) to set expectations from day one.

- Lifecycle accounting

Modern LCA tools recognize that concrete can reabsorb some CO₂ through carbonation over time and especially when crushed at end-of-life. Track what you divert and reuse; it’s valuable for ESG reporting and future design improvements.

Why this approach pays off (without talking dollars):

- Concrete may be a small line item in houses and small plazas, but it determines how long the asset lasts and how often you’ll be interrupted by repairs.

- The cheapest path is nearly always to design for durability, build with discipline, and maintain lightly, instead of rebuilding early.

- Treat each element like a long-term service: design it to resist the environment, document what you built, watch for early signs, and plan a circular end of life.

New Materials & Knowledge Optimization

The field of concrete is dynamic, with new materials emerging and a constant need for industry professionals to optimize their knowledge. Staying ahead of these developments can confer significant advantages in performance, sustainability, and cost.

Let’s explore some cutting-edge materials making waves, and discuss how leaders can keep their organizations’ concrete expertise sharp.

Emerging Concrete Materials:

- Fiber-Reinforced Concrete (FRC)

Recent fiber technologies allow concrete to deform more before cracking, offering better crack control and improved durability.

- Graphene-Enhanced Concrete

Small amounts of graphene can significantly increase strength and modify electrical or thermal behavior, creating opportunities for high-performance or smart applications.

- 3D-Printable Concrete Mixtures

Specialized mixes with rapid-set and thixotropic properties allow concrete to be extruded in layers, enabling formwork-free construction.

- Geopolymer and Alkali-Activated Binders

Cement-free binders made from materials like fly ash can deliver major CO₂ reductions, with growing interest in scaling their use.

- Self-Healing Concrete

Capsules or bacteria embedded in the mix can seal small cracks automatically, reducing maintenance and extending service life.

- Translucent Concrete

Concrete with embedded light-transmitting elements creates panels that pass light while maintaining structural form.

- Phase-Change Material (PCM) Concrete

PCMs incorporated into concrete can absorb and release heat, helping stabilize indoor temperatures and improve energy performance.

Conclusion

Concrete is more than a cost item. It is the material our roads, hospitals, data centers, water plants, schools, ports, and power systems are literally made of. When concrete performs, cities grow, businesses run, and communities feel safe. When it fails, we see closures, detours, costly repairs, and in some cases disasters that stay in the news for years. Understanding how concrete behaves, ages, and improves is a key part of effective leadership.

The industry is also evolving quickly. Smarter mix designs, durability-focused specifications, low-carbon materials, sensors, and new technologies are giving teams greater control over performance, cost, and environmental impact. Leaders who stay curious, keep their teams learning, and adopt the right innovations see faster construction, longer lasting structures, stronger financial outcomes, and a reduced footprint. Learning concrete supports better projects and stronger, more resilient communities.

The construction industry is always innovating!

Learn how the latest technologies are optimizing concrete workflows and performance in our Construction Revolution Podcast.