Concrete’s hectic morning shows a simple truth: plant to pour is a carefully managed journey, not just a delivery. From batching and mixing to transport, placement, and curing, every step affects the next. Concrete doesn’t wait. The instant water hits cement, the mix starts transforming, and there’s no undoing a batch that isn’t managed correctly.

Want to take the guesswork out of concrete slump?

According to the National Ready Mixed Concrete Association (NRMCA), fresh concrete is a perishable product: it can lose slump and stiffen as time passes, especially in hot weather or during long hauls. Concrete doesn’t arrive at the jobsite in perfect stasis; it’s changing every minute as hydration progresses. Because of this, industry standards have long treated delivery with precision. ASTM C94 historically set a 90-minute limit from mixing to discharge to ensure concrete stayed workable and hadn’t begun to set. Exceeding that window often meant rejecting the load, a costly outcome when traffic or onsite delays interfered.

Today, admixtures and updated standards allow more flexibility. If slump, temperature, and air content remain within spec, producers and contractors can extend delivery times, sometimes beyond 120 minutes. But the principle remains: concrete moves steadily from fluid to solid, and that transformation must be carefully managed.

This blog follows that journey from plant to pour to show how every stage shapes the final result.

The Clock Starts Ticking at the Plant

5:42 AM. A pale sky hangs over a half-formed foundation as the crew checks their watches. The first truck was due at 5:30. It’s now 12 minutes late. Nobody says much, but everyone knows those 12 minutes are eating into a tight finishing window.

Headlights finally sweep across the site. The superintendent breathes out, equal parts relief and annoyance. That short delay means hotter sun during finishing, a greater chance the next trucks bunch up or hit traffic, and overtime creeping closer. The pump crew is waiting. The lab tech’s 6:00 AM test slot is already in question. A small slip at the start is rippling through the schedule.

By 5:52, concrete flows from the chute, but the damage is done: less time to place and trowel, more pressure on every decision. On this kind of job, timing isn’t a detail. It’s the whole game – because concrete isn’t just delivered. It’s a ticking chemical clock that has to be managed from plant to final trowel.

Inside the Ready-Mix Plant: Where the Journey Begins

A successful pour starts long before the truck arrives. At 5:00 AM, the ready-mix plant is already alive: cement towers above, aggregates wait in sorted piles, and operators carefully measure and mix materials, balancing precision and experience to produce concrete ready for the journey ahead.

Mix Design and Proportioning

Concrete begins with a simple but carefully balanced recipe:

- Ingredients: Cement, water, fine and coarse aggregates, and often admixtures or supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) like fly ash or slag.

- Proportioning: Project specifications or plant-selected designs determine proportions to achieve strength, workability, and durability at minimal cost.

- Moisture Control: Moisture in stockpiles is closely monitored. Sudden rain or overly dry aggregates can drastically affect slump and consistency, impacting the quality of concrete that reaches the slab.

Supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs)

SCMs are commonly added to replace a portion of Portland cement.

- Common SCMs: Fly ash, slag, silica fume.

- Benefits: Improve workability, reduce heat buildup, enhance durability, and improve pumpability.

- Usage: Modern mixes often contain 15–30% SCMs, which also help reduce costs and carbon footprint.

- Considerations:

- Class F fly ash can slow early strength in cold weather.

- Slag may change set time and concrete color.

- Quality Control: Teams verify correct type and dosage since small deviations can affect workability and setting behavior.

Admixtures

Chemical admixtures fine-tune concrete performance for specific conditions.

- Types and Purpose:

- Water-reducers: improve workability.

- Retarders: delay setting for hot weather or long transportation.

- Accelerators: speed set in cold conditions.

- Air-entraining agents: protect against freeze-thaw cycles.

- Precision Matters:

- Dosed in small, precise amounts using computerized systems.

- Errors can cause serious problems (e.g., mistyped retarder delays setting for 36+ hours; incorrect air content can lead to surface scaling).

- QA/QC Practices:

- Routine equipment calibration.

- Batch documentation for consistency and traceability.

Modern plants are increasingly leveraging AI-based solutions like SmartMix™ to optimize concrete mix designs. SmartMix balances cement, water, aggregates, and admixtures to achieve the target strength, workability, and durability, all while minimizing cost and carbon footprint. Using predictive analytics, it ensures each batch meets specifications before it even leaves the plant.

Mixing Methods

Concrete mixing can follow different methods depending on plant setup, project requirements, and desired consistency. Each approach, central mix, transit mix, or shrink mix, affects quality control, speed, and efficiency. Below is a clear breakdown of how each method works and what happens before a truck leaves the plant.

| Method | How It Works | Key Advantages | Notes / Requirements |

| Transit Mix (Dry Batch) | Dry ingredients + most water are loaded into the truck. Mixing occurs in the rotating drum during transit or on site. | – Allows slump adjustments on site- Flexible for longer travel distances | Requires high-speed mixing (≈70+ drum revolutions) to fully homogenize; must follow ASTM C94 uniformity requirements. |

| Central Mix (Wet Batch) | A large stationary mixer blends the concrete before discharging into trucks. | – Highly consistent loads- Ideal for high-volume placements- Reduces wear on truck drums | Used by ~20% of U.S. plants. Plant can prepare next batch while trucks deliver. |

| Shrink Mix (Hybrid) | Concrete is partially mixed at the plant, then final mixing occurs in the truck. | – Reduces truck mixing load- Increases plant throughput | Must still meet ASTM C94 mixing requirements for uniformity and drum revolution limits. |

Before a truck leaves the plant, a quick inspection ensures the load meets specifications. The dispatcher checks temperature control, verifies admixtures such as stabilizers, and confirms the slump is close to the target. Many plants batch slightly low slump, allowing small on-site adjustments. Raising slump with water or admixtures is best done at the plant where mixing is controlled. Once everything is verified, the driver washes down any residue, climbs into the cab, and heads out. The concrete’s journey is officially underway.

What Happens When the Concrete is In Transit?

The moment the truck pulls away, hydration is already underway. As water reacts with cement, microscopic compounds start forming, which is the early stages of the solid structure that the concrete will eventually become. Even though concrete remains workable for several hours, its properties shift continuously.

The 60-90 Minute Guideline

Producers generally plan for transit times of 60 to 90 minutes. This benchmark comes from decades of field experience: within this window, concrete stays workable if the drum keeps rotating. Agitation prevents segregation and keeps the mix cohesive.

Beyond 90 minutes, risks rise sharply. Slump may drop too far, early set may begin, and loads may need to be rejected. While modern admixtures and updated standards allow more flexibility, sometimes extending workable time past 120 minutes, the principle remains the same: concrete must be delivered or discharged before its quality margin narrows.

Hydration, Heat, and Temperature Control

Hydration produces heat, so a long-haul mixer load often feels warm to the touch. High temperatures accelerate setting and slump loss, making hot weather a significant concern. Drivers will sometimes park in shade or momentarily increase drum speed during long stops to minimize localized heating and settlement.

For extreme climates or long deliveries, producers may insulate the drum or cool the mix with techniques such as chilled water, ice, or even injected liquid nitrogen. These strategies slow the temperature rise and protect workability.

Drum Rotation: Finding the Right Balance

During transit, the drum must rotate continuously, usually between 2 and 6 RPM, to maintain uniformity. Too little rotation and the mix can segregate or begin to stiffen. Too much rotation and the mix may entrain excess air or mechanically grind the aggregates, causing slump loss.

Older standards limit total drum revolutions (~300) to prevent over-mixing. Higher speeds are only used briefly for initial mixing or re-mixing at the jobsite.

Slump Loss in Transit

Losing slump in transit is normal. The rate depends on mix design, weather, and admixtures. Heat is the biggest factor: at 90°F (32°C), slump can drop twice as fast as at 60°F (16°C). Wind and low humidity also draw moisture from the concrete if the drum seal isn’t tight.

A 4-inch slump mix may lose an inch in moderate conditions within an hour. Some admixtures, such as superplasticizers, lose effectiveness after 30-60 minutes, leading to a sudden slump drop unless re-dosed.

Modern mixer trucks equipped with MixPilot™ a self-calibrating in-transit sensor that continuously monitors slump and workability. This sensor allows field teams to adjust admixtures safely and in real time, essentially turning the truck into a mobile, intelligent batching unit.

Traffic, Delays, and Communication

Transit challenges aren’t only chemical; they’re logistical. Drivers constantly coordinate with dispatch and the jobsite. A call ahead helps crews stage pumps, finishers, and testing personnel.

If traffic delays threaten quality, dispatch may reroute the truck or return it to the plant. Hydration stabilizers can slow setting when delays are unavoidable, and water or admixtures may be added within specified limits, always recorded to maintain accountability.

By the time the truck arrives, even a short delay, like the 12-minute lag in our opening story: it can translate into higher temperature, lower slump, and tighter finishing windows. Managing concrete’s evolution during transit is critical to ensuring quality at the pour.

Minimize uncertainty on long or delayed deliveries with MixPilot. Read the full blog on in-transit monitoring here!

Arrival at the Jobsite: Moment of Truth

When a concrete truck reaches the jobsite, the process shifts into a critical phase: evaluation and coordination. The crew has prepared the forms or slab base, and often the previous load is already in place, waiting for the next batch to continue the pour. But before any concrete is discharged, a quick but essential sequence of checks begins. This step blends quality control, communication, and timing to ensure the load is acceptable and ready to place.

Staging and Site Prep

Positioning the truck is often the first challenge. On tight or busy sites, spotters guide the driver through rebar cages, trenches, or congested access lanes to reach the chute location or pump hopper. A designated washout pit is usually prepared in advance for cleaning after unloading.

If multiple trucks are queued, their order is planned to keep unloading intervals consistent. Too many arriving at once leads to delays and slump loss inside the drums; spacing them too far apart risks cold joints in the pour. Dispatch aims for a steady rhythm; often 5 to 10 minutes between trucks, balancing logistics and concrete performance.

Slump and Air Testing (Acceptance Sampling)

Before unloading begins, a field technician typically samples the concrete. Standard practice is to discharge a small initial amount, then collect a representative sample for testing. The technician performs slump, air content, and temperature tests and compares the results with the project specifications.

If slump or air content is low:

- Water or air-entraining admixture may be added.

- At least 30 revolutions of mixing are required to ensure uniformity.

- Adjustments must occur early in the discharge to maintain consistency across the load.

If slump or air content is too high:

- Correction is difficult: water cannot be removed, and air cannot easily be reduced.

- A second test may be performed to confirm the first reading.

- If still out of tolerance, the load may be rejected to protect long-term concrete quality (strength, durability, and surface performance).

Communication and Load Acceptance

Once the load meets requirements, the contractor’s representative signs the delivery ticket. Any adjustments, such as added gallons of water or on-site admixture, must be documented for accountability. If the load fails or arrives too late, it may be sent back. Most teams try to prevent this outcome through careful scheduling and proactive communication with dispatch.

Jobsite Water: Handle With Caution

Adding water on site is allowed but tightly controlled. A small, documented amount can fine-tune workability, but too much water reduces strength, increases cracking risk, and extends set time. One extra gallon can increase slump noticeably while reducing compressive strength by several hundred psi. When additional workability is required beyond allowable water limits, a water-reducing admixture is the proper option. Some projects even keep a supervised admixture station on site for this purpose.

Being Prepared for the Unexpected

Even with planning, unexpected conditions arise. Technicians may check density for yield calculations or cast strength cylinders. Early test results often guide adjustments for subsequent loads: a low air reading may prompt the plant to increase air-entrainer dosage; a high slump may lead to slight reductions in water content for following trucks.

This feedback loop is one reason many projects prefer testing at the truck chute; it allows corrections in real time. Ideally, these expectations are established during a pre-placement meeting, ensuring all parties understand target slump, acceptance criteria, and contingency plans.

Placement Methods Do’s and Don’ts: From Chutes to Booms

Getting concrete out of the truck is only the start. The real challenge is placing it exactly where it needs to go into every corner of the forms, around rebar, and across a slab without segregation or cold joints. Different placement methods suit different sites, and each has clear practices to follow and pitfalls to avoid. Here are some most common methods:

| Method | Best For | How It Works | Pros | Limitations / Considerations |

| Direct Pouring (Chute Discharge) | Driveways, sidewalks, footings, ground-level slabs | Truck backs in; concrete flows by gravity from the chute while crew spreads and guides | – Fast setup – No extra equipment – Minimal labor | – Chute reach ≈ 16 ft – Truck must get very close – Steep angles can cause segregation – Not suitable for hard-to-reach or elevated areas |

| Line Pump | Residential work, interior pours, tight-access sites | Concrete is pushed through hoses laid along the ground or through doorways/corners | – Compact and flexible – Good for confined areas – Controlled placement rate | – Slower than boom pumps – Requires hose setup and cleaning |

| Boom Pump | Large pours, structural slabs, high-reach areas, bridge decks | Truck-mounted boom places concrete from above via an articulated arm | – Long reach (20–60+ m) – Fast, continuous placement – Ideal for critical structural timing | – Needs space for outriggers – Higher cost – More setup/cleanup time – May require permits or lane closures |

| Crane & Bucket | High-rises, core walls, tight urban lots | Truck fills a steel bucket; crane lifts and dumps into forms | – Uses existing crane – Reaches deep/complex formwork – Good when pump access is limited | – Slower (bucket-by-bucket) – Buckets often partially filled – Requires strong coordination & safety – Ties up the crane from other lifts |

Quality Management During Placement

| Issue | Best Practices |

| Segregation & Air Loss | Avoid long drops; limit rehandling; account for predictable air loss through pump lines without over-airing. |

| Cold Joints | Place concrete in controlled layers; maintain continuous placement rhythm. |

| Consolidation | Use internal vibrators to remove trapped air; avoid over-vibration to prevent segregation. |

| Finishing | Screed and bull float to level the surface and manage bleed water. |

Want to take the guesswork out of concrete slump?

Challenging Environments: When Plant-to-Pour Isn’t Easy

Not all concrete journeys happen on a mild day with a plant around the corner. Often, the “plant to pour” process is stretched to its limits by site constraints, traffic, temperature, or distance. In these conditions, concrete still has to meet the same performance requirements, but everything around it gets harder. Below are some of the most common challenging scenarios and how they shape decisions from batching to curing.

| Environment | Challenges | Plant Strategies | Transit Strategies | On-Site Practices |

| Urban / Dense Cities | In dense cities, concrete delivery is constrained by permits, traffic regulations, and noise bylaws. Trucks may only be allowed on certain streets at specific times, and setup for pumping often requires strict traffic and pedestrian control. Narrow delivery windows mean that any delay can cause crews to stand down, reschedule, and absorb significant costs, while travel times fluctuate widely depending on traffic conditions. | Producers often build traffic buffers into their scheduling and use extended-set or hydration-stabilizing admixtures to maintain workability if a truck is delayed. Project-specific delivery time limits are set rather than relying on a single standard number, provided slump, air, and temperature remain within specification. | Transit planning emphasizes coordination of street permits, pump locations, pedestrian control, and the use of spotters to safely navigate congested areas. Timing is critical to ensure the concrete arrives during its workable window. | On-site practices rely on precise coordination among dispatch, site teams, inspectors, and city authorities. The crew must be ready to receive, test, and place concrete efficiently within the narrow urban time window. |

| Remote / Long-Haul Projects | Remote sites such as wind farms, mountain bridges, or rural infrastructure face challenges primarily related to distance. The nearest ready-mix plant may be dozens of miles away, with access routes that are steep, unpaved, or otherwise difficult. Long travel times increase the risk of slump loss or early setting of the concrete. | Plants commonly use retarders or hydration stabilizers to slow hydration, chilled water, ice, or cooled aggregates to lower initial temperature, and adjust cement or SCM content to control heat of hydration. Satellite or temporary batch plants may be established closer to the project when volumes justify it. | During transit, crews plan pours during cooler periods and ensure that batch sizes and schedules minimize the risk of overextending any truck or crew. Contingency admixtures are kept on hand to maintain workability. | On-site, crews monitor slump and workability carefully, ensuring the concrete can be placed efficiently despite long transport times. Conservative batch sizes and timing help prevent partially set or unworkable concrete. |

| Hot Weather (ACI 305.1-14) | High temperatures, low humidity, wind, and direct sun accelerate evaporation and hydration, resulting in faster slump loss, shorter placing windows, and increased risk of plastic shrinkage cracking. Internal temperatures can reduce long-term strength if not controlled. | At the plant, chilled water, ice, or cooled aggregates are used to reduce concrete temperature. Retarding or slump-retention admixtures are incorporated to extend workability, total cement content is limited, and SCMs are used to reduce heat generation. Batching is often scheduled for early morning or night to ensure cooler placement. | During transit, unnecessary delays are avoided, drums are kept shaded, and steady agitation maintains uniformity. Temperature monitoring allows crews to adjust placement rate or curing practices if concrete approaches the upper temperature limit. | On-site, finishing crews are ready before the first truck arrives. Surface treatments such as fogging, evaporation retarders, windbreaks, and sunshades are used to limit drying. Curing begins immediately with wet coverings or curing compounds, and adding extra water on-site is avoided to prevent weakening the concrete. |

| Cold Weather (ACI 306R-16) | Cold weather slows hydration and early strength gain, with the risk of freezing before adequate strength develops. Frozen concrete can suffer internal damage and permanent strength reduction. | At the plant, heated water and aggregates are used, and non-chloride accelerators or high-early-strength cement may be incorporated to speed early strength gain. Slump is targeted moderately to limit bleed water that could freeze. | During transport, truck drums are cleared of ice or snow, transit time is minimized, and loads are protected from cold air and wind. In extreme cold, concrete may be batched slightly warmer with the expectation it will cool to a safe placement temperature. | On-site, snow and ice are removed from forms and subgrade. Windbreaks, enclosures, and indirect heaters protect the pour area, and fresh concrete is covered with insulating blankets or wet burlap plus plastic to retain heat. Temperature is monitored carefully during curing, and rapid cooling is avoided. Plasticizers are used instead of water to improve workability. The protection phase can last several days until the concrete reaches safe strength. |

Regardless of environment: urban, remote, hot, or cold, the principles of concrete remain the same, but plant-to-pour strategies must adapt. Success relies on anticipating how conditions affect hydration, slump, transport, and curing, and planning mix, schedule, and site practices accordingly. Proper finishing and curing ultimately determine whether the concrete achieves its intended durability and quality.

After the Pour: Finishing, Curing, and Early Protection

The concrete is in the forms or on the slab base; the truck’s job is done, but the concrete’s journey is not. Over the next few hours, it moves from soft and workable to strong and permanent. This is the most fragile stage of its life. How the crew finishes and cures the concrete will decide whether it performs well for decades or fails early.

Finishing Operations

Once concrete is placed, the crew levels it to the correct height (screeding) and then smooths it using tools like bull floats or darbys. For slabs and flatwork, they must also manage bleed water, the thin film of water that rises to the surface as heavier particles settle. This usually happens in the first 30 minutes to 2 hours.

A critical rule:

- Do not start final finishing while bleed water is present. Troweling too early forces water back into the surface, weakening the top layer and causing flaking or dusting.

- Wait until the surface is damp, not shiny. Excess water can be gently removed with squeegees or light air movement.

Once the bleed water is gone, the crew can:

- Float and trowel for a smooth finish (interior slabs, floors).

- Broom the surface for slip resistance (sidewalks, driveways).

- Edge and joint the slab, either by hand tools while the concrete is still soft or later by saw-cutting control joints.

For formed surfaces like walls and columns, “finishing” is often simpler: stripping forms at the right time, patching small voids (bugholes), and preparing surfaces for coatings or finishes. But these elements still need proper curing to perform as designed.

Timing varies with the weather:

- In hot conditions, bleed water disappears quickly and concrete sets faster, so finishing must keep pace.

- In cold weather, bleed water lingers, and set is slower, so crews must be patient and avoid rushing.

The Importance of Curing

Curing is the process of keeping concrete at the right moisture and temperature so cement can fully hydrate and the concrete can reach its potential strength and durability.

Why it matters:

- If concrete dries too fast, hydration stops, producing weak, porous surfaces prone to cracking, dusting, or scaling.

- Curing is one-shot; once early hydration is interrupted, concrete cannot be “re-cured.”

Curing is the final stage of the plant-to-pour journey, and it determines how well the concrete develops strength and durability.

- Moist curing: Continuous wetting using misting, fogging, soaker hoses, or light ponding. Prevents moisture loss and produces dense, durable concrete.

- Wet coverings: Burlap, cotton mats, or curing blankets hold moisture and slow evaporation. Blankets also provide insulation in cold weather.

- Curing compounds: Spray-applied liquids form a thin membrane to trap moisture. White pigments reflect sunlight and indicate coverage; clear versions act as temporary sealers.

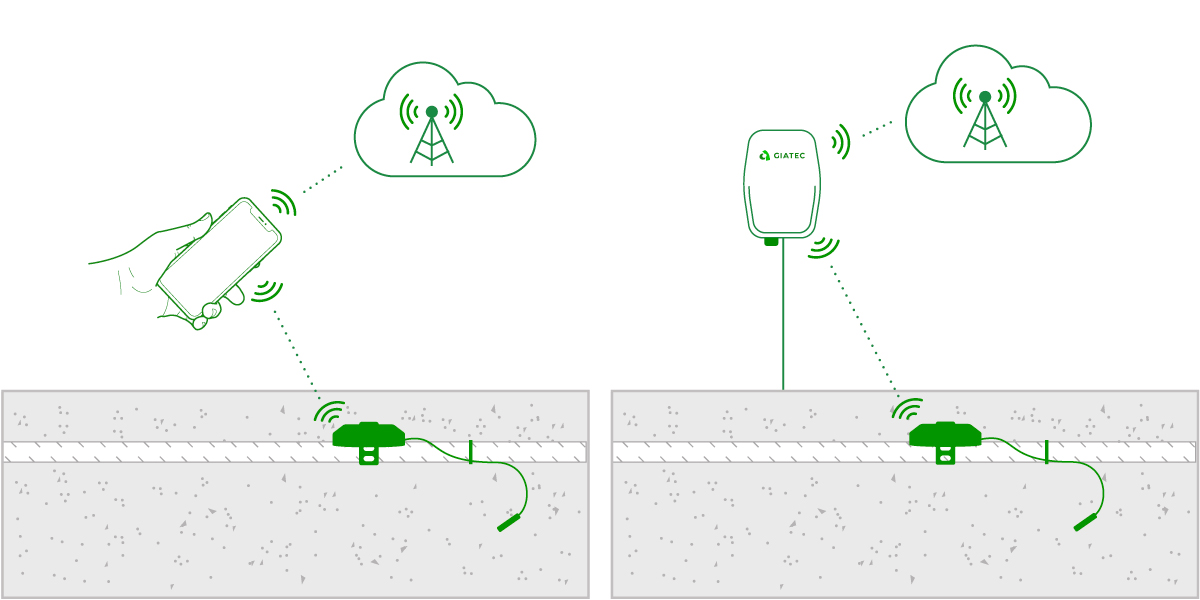

Want to achieve the best concrete quality of your pour? Discover how SmartRock® sensors give real-time insights to optimize curing and strength.

Early Protection and Avoiding Disturbance

In the first 24 to 48 hours, newly placed concrete is gaining strength but remains highly vulnerable. Early loading, premature form removal, or nearby impact can trigger cracking or hidden damage that affects long-term performance. Most specifications set minimum curing periods and required strengths before placing loads or stripping supports, and following these limits is essential for durable results.

Sidebar: Early Test Cylinders

Strength test cylinders cast during placement are used to confirm that the concrete reaches its design strength. For the results to be meaningful, cylinders themselves must be properly cured.

Typically, cylinders are kept on site in a moist, moderate-temperature environment for the first 24-48 hours, then moved to a lab for controlled curing until testing at 7, 28, or other specified days. If they dry out, bake in the sun, or freeze on site, the test results will show artificially low strengths.

Field-cured cylinders (stored under the same conditions as the structure) are sometimes used to decide when to strip forms or post-tension. If those cylinders are mishandled, they can lead to wrong decisions about when the in-place concrete is ready.

Conclusion

Think back to that first tense morning when a 12-minute delay threatened the entire pour. Weeks later, the same crew delivers a flawless slab because every step from batching and traffic planning to testing, placement, and curing was actively managed. The difference wasn’t luck; it was coordination. When concrete is guided, not merely delivered, each handoff strengthens the next.

Take control of your concrete from plant to pour! Listen to our podcast and discover how MixPilot and Digital Fleet bring real-time insights to every load.