Closely monitoring concrete temperatures is critical for ensuring proper strength development of concrete structures and concrete sustainability regardless of their application or size. However, when it comes to mass concrete structures, temperature differentials also need to be considered due to the risk of a large difference between the relatively hot internal temperature and cool surface temperature. If a too-large temperature differential occurs, the surface of mass concrete will start cracking, which is detrimental to its durability and the length of its service life.

Build Data Centers Faster with SmartRock® Long Range

What Is Mass Concrete?

Mass concrete is not defined by any specific measurements. According to the American Concrete Institute (ACI), mass concrete is “any volume of concrete with dimensions large enough to require that measures be taken to cope with generation of heat from hydration of the cement and attendant volume change to minimize cracking.” Some examples of mass concrete include dams, large bridge piers and columns, mat slabs and foundations.

Learn how to elevate your mass concrete projects here!

It’s important to note that smaller structures may also be categorized as mass concrete depending on several factors, such as type and quantity of cement, volume to surface ratio of the concrete, weather conditions, concrete placing temperatures, degree of restraints to volume changes, and the effect of thermal cracking on function, durability and appearance.

Why Is It Important to Monitor Mass Concrete Temperature?

In order to ensure that mass concrete properly cures to reach adequate strength, it must be poured when the ambient temperature is between 50-60 °F (10-16 °C). If the temperature is too low, the chemical reactions that strengthen the concrete slow down significantly and, at a certain point, come to a complete stop. If the temperature is too high, it will cause the concrete to have high early strength development but consequently gain less strength in the later stages, resulting in lower overall durability of the structure.

How Do Temperature Differentials Affect Mass Concrete?

As concrete hydrates and hardens, it generates heat. When constructing mass concrete structures, significant tensile stresses and strains are likely to develop due to the difference between the structure’s core temperature and surface temperature (this difference is known as the temperature differential). These stresses occur because the volume of the warmer concrete expands while the cooler concrete contracts.

The likelihood of thermal cracking increases as the inner core of the mass concrete continues to heat (hydration) while the outer surface of the concrete cools (heat dissipation). This is exacerbated by extreme cold weather, which quickly cools the outer surface of the concrete, but does not reach the inner core.

Learn more about thermal cracking here!

According to ACI 301-16: Specifications for Structural Concrete, the maximum concrete temperature differential should not exceed 35 °F (19 °C) during curing. In most situations, this approach is very conservative, but in other cases, it can be an overestimation of the allowable temperature differential.

Without monitoring temperature differentials in mass concrete, contractors and project managers could run into serious problems such as cracking, reduced service life, project delays and noncompliance. These problems can make it hard to have a sustainable concrete construction.

Build Data Centers Faster with SmartRock® Long Range

What’s the Best Way to Monitor Temperature Differentials?

On construction sites, temperature differentials are normally measured using thermocouples or data loggers. Unfortunately, using these tools to collect data and subsequently analyzing the data on a computer becomes quite time-consuming, which negatively impacts a project’s schedule.

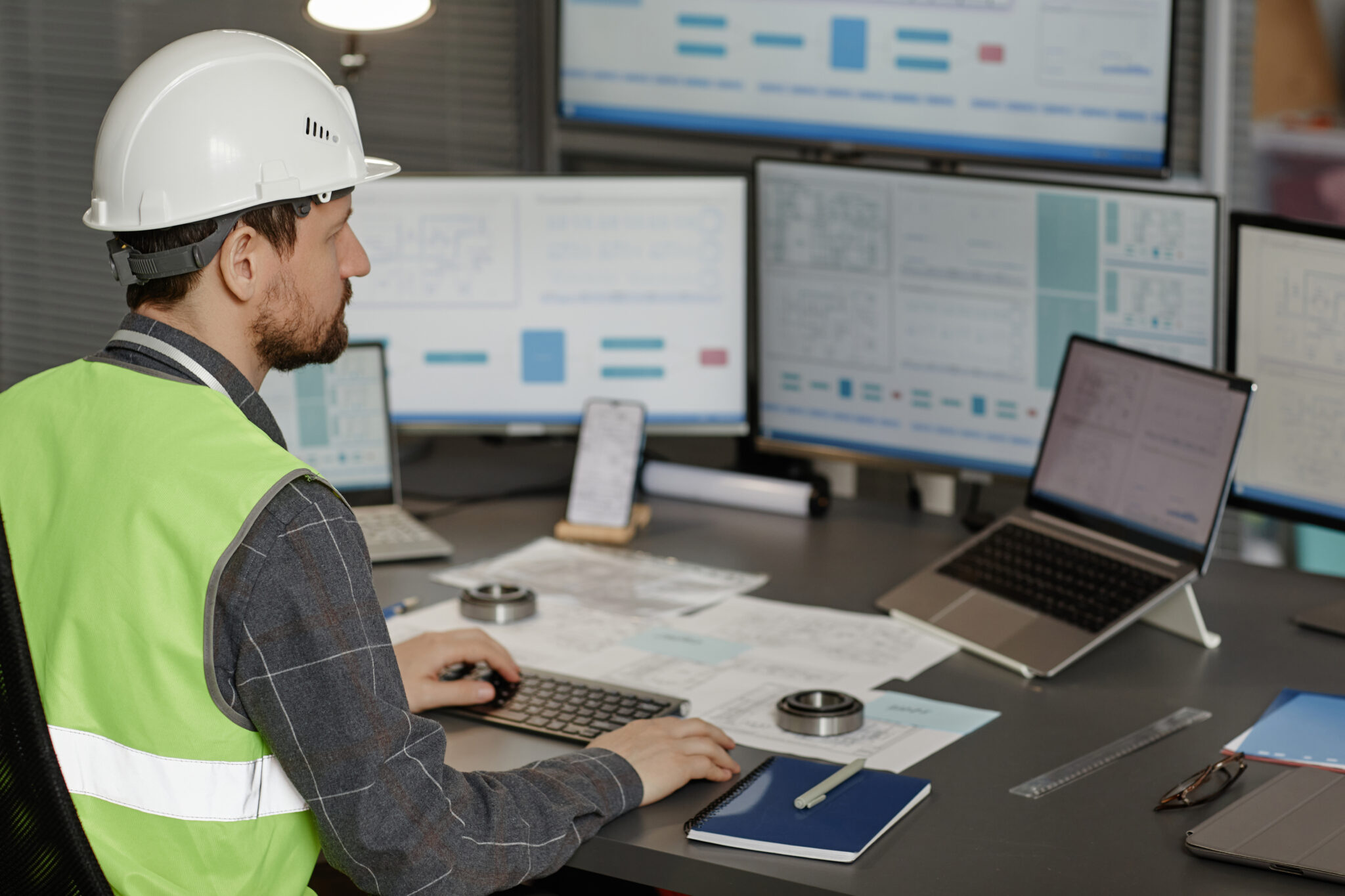

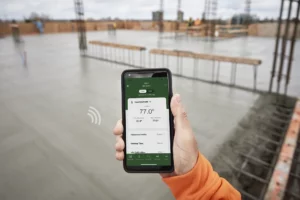

Fortunately, contractors and engineers can take advantage of advanced technology that uses the maturity method to monitor concrete temperatures. One such technology is Giatec’s SmartRock®, which has now been re-engineered with innovative dual-temperature capabilities. This trusted wireless sensor, used on over 6,200 sites worldwide, is installed on the rebar before a mass concrete pour and enables the measurement of concrete temperatures in two locations simultaneously.

These easy-to-install sensors offer precise real-time temperature readings for mass concrete pours at the surface and center of the slab, which are immediately sent to the user’s mobile device.

For greater control over the monitoring and analysis of mass concrete element temperatures, project owners and contractors can complement SmartRock with SmartHub™, a remote monitoring system that allows users to access SmartRock data any time, anywhere (even off-site).

Read more about SmartHub here!

Why Are Temperature Differentials in Mass Concrete So Important in Winter?

In ACI 306: Guide to Cold Weather Concreting, cold weather concreting is defined as “a period when for more than three successive days the average daily air temperature drops below 40°F (5°C) and stays below 50°F (10°C) for more than one-half of any 24 hour period.”

In addition to slowing down the curing process, cold weather also causes the water in concrete to freeze and expand, cracking and weakening the concrete. In some cases, the concrete may even be rendered useless. However, it can still be successfully poured and placed in winter as long as the right precautions are taken to heat it properly.

Here are a few tips on how to control the temperature of your concrete in cold weather:

- Keep the concrete in a dry and heated area until it’s ready to use.

- Install internal electric heating: This requires using embedded coils and insulated electrical resistors.

- Optimize your concrete mix: Using low-heat cement; aggregate substitutes such as fly ash, limestone, or slag; and a low water-to-cementitious materials ratio are all good ways to optimize your concrete mix for heat retention in cold weather.

- Use insulation: Layering helps maintain the heat that is generated from the concrete. Insulation methods like heating blankets or forms allow you to control temperature differentials between the core and the surface of your slab.

- Cool your mass concrete pour before placement: This can be done using chilled water, chipped or shaved ice, or liquid nitrogen.

- Cool the concrete after placement: Use embedded non-corrosive cooling pipes prior to concrete placement. This removes heat by circulating cool water from a nearby source.

- Remove standing water: Bleed water needs to evaporate or be removed by a squeegee or vacuum.

For more tips on cold weather concreting, see our blog on 7 common mistakes to avoid in cold weather concreting!

Hot Weather Concreting

Generally, a concrete temperature is limited to 70°C (160°F) during hydration. If the temperature of the concrete during hydration is too high, it will cause the concrete to have high early strength development but consequently gain less strength in the later stage, resulting in lower durability of the structure overall. Furthermore, it has been observed that such temperatures interfere with the formation of ettringite in the initial stage and subsequently its formation in the later stages is promoted; which causes an expansive reaction and subsequent cracking.

Additionally, high temperature issues are of concern, especially in mass concrete pours, where the core temperature can be very high due to the mass effect, while the surface temperature is lower. This causes a temperature gradient between the surface and the core, if this differential in temperature is too large it will cause thermal cracking.

The first step to ensuring adequate strength gain of mass concrete in cold weather is to gather accurate data. With SmartRock’s dual-temperature functionality, users are equipped with the data they need to inform them when their mass concrete reaches critical temperatures and how much it needs to be heated.

**Editor’s Note: This post was originally published on November 2020 and has been updated for accuracy and comprehensiveness