Precisely monitor the temperature of your concrete structures under any conditions

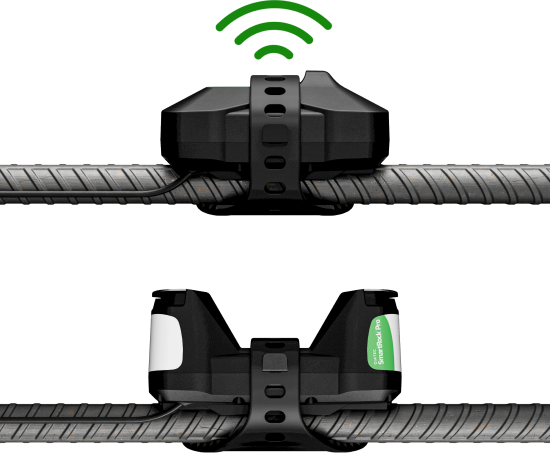

Collect real-time in-situ concrete strength data through maturity-based sensors

Maturity-Based Concrete Strength Monitoring

Self-Calibrating Concrete Strength Monitoring

AI-powered precision for every concrete mix for the Producers

Instant ROI

AI-Powered Decision Making

Drive Sustainability

Core Quality Control

Corrosion detection in concrete reinforcement

Concrete quality detection lab equipment

Quality That Travels from Plant to Pour

Devices for Measuring Rebar Corrosion, Permeability, and Resistivity of Concrete

Experts revolutionizing the construction industry

Stay on the cutting edge of concrete tech

Save the date and join us at future events and conferences

Mass concrete temperature differentials are one of the leading causes of thermal cracking in large concrete pours. When the internal core heats up during hydration while surface temperatures cool, tensile stresses develop that concrete cannot withstand. Without proper monitoring, these stresses result in early-age cracking, reduced durability, and costly repairs. Closely monitoring concrete temperatures is critical for ensuring proper strength development of concrete structures and concrete sustainability regardless of their application or size. However, when it comes to mass concrete structures, we need to consider temperature differentials due to the risk of a large difference between the relatively hot internal temperature and the cool surface temperature. If a too-large temperature differential occurs, the surface of mass concrete will start cracking. This is detrimental to its durability and the length of its service life. In this blog, let’s take a look at why managing mass concrete temperature differentials is important for preventing thermal cracking and ensuring long-term structural durability. What Is Mass Concrete? Mass concrete is not defined by any specific measurements. According to the American Concrete Institute (ACI), mass concrete is “any volume of concrete with dimensions large enough to require that measures be taken to cope with the generation…

Concrete’s hectic morning shows a simple truth: plant to pour is a carefully managed journey, not just a delivery. From batching and mixing to transport, placement, and curing, every step affects the next. Concrete doesn’t wait. The instant water hits cement, the mix starts transforming, and there’s no undoing a batch that isn’t managed correctly. According to the National Ready Mixed Concrete Association (NRMCA), fresh concrete is a perishable product: it can lose slump and stiffen as time passes, especially in hot weather or during long hauls. Concrete doesn’t arrive at the jobsite in perfect stasis; it’s changing every minute as hydration progresses. Because of this, industry standards have long treated delivery with precision. ASTM C94 historically set a 90-minute limit from mixing to discharge to ensure concrete stayed workable and hadn’t begun to set. Exceeding that window often meant rejecting the load, a costly outcome when traffic or onsite delays interfered. Today, admixtures and updated standards allow more flexibility. If slump, temperature, and air content remain within spec, producers and contractors can extend delivery times, sometimes beyond 120 minutes. But the principle remains: concrete moves steadily from fluid to solid, and that transformation must be carefully managed. This blog…

Giatec continues to uphold the value of bridging the gap between academic research and sustainable construction on the jobsite. Every year, we recognize civil engineering students, researchers and faculty across Canada and the U.S. with the Giatec Best Paper Award for Sustainability in Construction. Below is a summary of the winning 2025 paper submitted by Dr. Soroush Mahjoubi and his team, “Data-Driven Material Screening of Secondary and Natural Cementitious Precursors.” Want to see how you can share your research for the 2026 Giatec Best Paper Awards? Learn more here! Research Background Concrete is the most widely used manufactured material on the planet, and because we produce so much of it, it has a significant carbon footprint. Most of those emissions come from clinker, the binder in cement that requires energy-intensive kilns and releases CO₂ when limestone is calcined. For decades, the industry has replaced a portion of clinker in mixes with lower-carbon materials such as coal fly ash and steel slag. However, as coal plants shut down and steel recycling ramps up, supplies of these traditional substitutes are shrinking. To continue reducing emissions by replacing clinker, the industry needs new supplies of clinker replacements. New research from the MIT Concrete Sustainability Hub and Olivetti Group aims to mitigate this problem with the help of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). The team used large language…

Visit our careers page to learn about our award-winning culture and our open positions.